Story construction standard fable

List of methods / Narrative methods

This method takes a naturalistic approach to story construction, replicating the way that we create stories through telling and retelling over time. The natural process is structured and time-compressed. Aside from teaching a basic skill, this approach can also be used to determine what type of communication strategy is most likely to work as well as providing a method to integrate the material in a workshop.

The method can be used stand-alone or with each stage distributed over a day or two days (in which case it provides a means to integrate and measure the learning that has taken place. In the latter case, the focus should be on the wider activity

Background

A fable is a long and complex story whose message is memorable but whose details are not. People who hear a fable cannot retell it exactly from memory, which helps the storyteller to maintain control over it. Anyone who has heard a fairy tale or folk story has heard a fable.

There are two messages in a fable. The obvious message is a memorable saying or moral, which is what the audience thinks the fable is about. The subtext message is more powerful yet hidden in the way things are described within the fable. For example, a fable about a rich man winning a business deal may be on the face of it "about" the virtues of ruthless competition, since the man may win his prize, but the underlying subtext may emphasize (through subtle glimpses of the man's empty emotional life) how worthless the prize turns out to be. Fables have been used to convey complex meanings like this for many thousands of years.

In a fable, the message comes at the end of the story (the subtext message comes throughout). In non-narrative communications, the message usually comes first, and then people don't listen to the details. In this way, a fable keeps the attention of listeners until it has delivered its full message.

Preparation

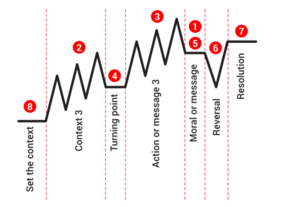

Normally a cabaret-style setting is suitable for Silent listening and Ritual dissent which are used in the approach. For historical reference, ritual dissent was originally created while running this process for corporate communication with a Canadian Company in Kasanakas, Canada. It may be useful to have record cards for the storyteller to keep notes. People should have whiteboards or paper and pencil to work with if they like (those are not strictly required for the exercise). It's also useful to have the fable form diagram drawn large so that everyone can see it, either on a flip chart or a chalkboard; or you can hand out copies of papers with it on them.

If used, the film clips identified below and also the extracts from McKee's book STORY which describe each scene.

Here you can download a printable worksheet for the process

Workflow

| Stage | COMMENTARY & TIPS |

| Familiarization with anecdotal material | Ask people to form small groups between four and eight people. Try to group people so that each group is as diverse as possible. For example, you might sort people by how long they have been with the organization (e.g. by asking them to line up), then recombine them.

Each group should work someplace where they can talk away from the noise of the other groups. Round tables are best, but people can also move their chairs to corners of the room or anywhere they feel they can work isolated from other groups. For this reason, it is best if the room has lots of extra space. Start by asking people to talk about anecdotes for a short time (c. 15 minutes). If people are using a pre-existing body of anecdotes, you will have distributed the anecdotes prior to the exercise so that everyone sees a variety of anecdotes, and every anecdote is seen by a variety of people. Alternatively, if you are doing the story construction "from scratch" and have no anecdotes to work from, ask people to start by talking about the topic of interest and telling anecdotes from their own experience. After fifteen minutes, ask people to decide on the abstract objective or purpose of the story they will tell. Ask them what they want the story to accomplish, what they want the audience to take away. It is sometimes useful to give them a scenario in which they have to tell the story (e.g., convince X that Y is necessary; you are presenting your point of view to a group of X; your X asks you to explain Y to them). Usually, the objective will relate to the topic being discussed in the workshop or project. Give only a short time (five or ten minutes) for this task. Alternatively, if your overall time is short, the objective can be chosen for all the stories and groups together, by yourself or by having people make suggestions and choosing one out of those. |

| Introduction of fable form | Now tell a fable story you have prepared, or show a video with one (you can find examples below). Show the fable form diagram and explain how the parts of the fable were represented in the story you just told or showed. Then explain the sequence in which people should put together the story elements. Make sure people understand the elements and sequence. Ask for questions, but don't get drawn into a long discussion about what is the best form, or where the form came from, and so on. Keep the introduction short and practical, centred around what people are going to be doing. |

| First construction | Ask the groups to begin working on their stories using the sequence you described. They should select their first three context anecdotes by the end of the first half-hour. All the anecdotes in the stories people construct should come from the anecdotes they "brought" with them, whether from a set they were exposed to or from their own experience.

As with many other types of emergent group exercise, people may have a hard time getting started. Remind them that they can change the contents of their story later, but that they need to get something in place before the first telling. The three context anecdotes are an easy group to select since they only need to match the context of the given topic. If people are unsure what anecdotes to choose or ask for a lot of guidance, just tell them to experiment with some anecdotes in their first telling, and they can change them later. The important thing is to just get started with something. |

| First telling | Ask each small group to appoint a storyteller who will visit the other groups and tell them the story in progress and an observer who will go with the storyteller and observe reactions. The storyteller must remain the same through all tellings.

Now ask the storyteller and observer from each group to go to the next group clockwise and tell their group's story, or whatever parts of it have been selected. Give them ten minutes to do this. The audience (the remainder of each group) may not comment on the story, though they may react non-verbally. In the telling, transferring the story message depends on a close link between the story and storyteller. That is why the storyteller must be the same for all tellings, and that is why the audience should not comment (so the storyteller can begin to build a relationship with the story by telling it uninterrupted). It is important to maintain control of perceptions about what the exercise is for. For example, we do not recommend that you tape storytellings, because it will create a feeling that there is a "right" story to tell or a "right" way to tell the story when what actually matters is diversity among stories, tellers, and tellings. In fact, it is important to get across to the groups that the entire exercise is more a matter of going through a process than creating a product. People are often astonished to learn that the story they have created is not going to be "saved" or taped or written down, although that is technically possible. The point of the exercise is not creating the right kind of story but getting at insights and perspectives during the process of creating. |

| Second construction | After the telling is finished, ask each storyteller and observer to return to their group and report on how the storytelling went. Tell the groups that they can revise their story on the basis of the report, changing any part they feel needs to be changed. At the same time, they should continue to place elements in it according to the sequence they were given. After they have the context three in place, they should select another three anecdotes for the action three, then move on to select an anecdote for the turning point.

You can't recombine groups if all the people in a group are not participating equally in story construction, since each group must stay together while it constructs a story. In this exercise, you just have to let groups be the way they are going to be to some extent. As long as the story is progressing, things should work out fine. One thing you could do is ask the people paying the least attention to story construction to do another activity (two-stage emergence, perhaps, or creating a Cynefin framework) that might also be useful for the overall sense-making purpose of the activity. As always, give a generic reason for doing this so that you are never targeting individual people or giving a negative reason for forming another group. |

| Second telling | After thirty minutes of work on the story, ask the storyteller and observer from each group to go to a different group this time (perhaps moving two groups over, or moving counter-clockwise) and tell the story, again taking ten minutes. After this, the storyteller and observer should again return and report the results. |

| More constructions and tellings | You can repeat the construction periods and telling (with reporting back) periods as many times as possible and desired, though a minimum of two times (one is not enough to get the idea) and a maximum of five times (more is usually not required) seem to be a useful boundary.

You can play with the placement of telling (moving people clockwise and counter-clockwise) to spread out who hears what story when, mostly to give the storyteller and observer the most diverse reactions possible. With later tellings, the "no audience comment" rule can be relaxed, and audiences can give constructive comments on how well the story works. Keep reminding people of the progress they should be making through the story construction sequence, i.e., in the second construction period they should complete the action three and perhaps the turning point; in the third period they should complete the turning point, moral, reversal and resolution; in subsequent tellings, they can add a context piece at the beginning and refine all the elements. How much of the story the groups complete will depend on the time you have available and the purpose of the exercise (whether sense-making or communication is the more important outcome). If you are able to do more than two rounds of story construction and telling, you can give people more to do than just throw anecdotes into slots: you can start asking them to start considering how they can improve the narrative form of their stories. As people start thinking about telling a better story, they do a few interesting things. First, they process and integrate more disparate material than they would if they weren't "improving" their story, bringing more elements together and making connections as part of the method. Second, by thinking about narrative form, people forget a little about analytical ways to carry out the form-filling task and allow emergent processes to work better. Third, concentrating on constructing a "good story" gives people another perspective on the issues they have been considering and may lead them to fresh insights. So, between construction-telling cycles, you can begin to interject some information about narrative form, such as a clip from a movie in which important narrative elements can be seen or just talk about things people might be wanting to take into account as they create their purposeful stories. If you don't know what to tell people, read McKee's Story for pointers. These movie clips contain good examples of narrative elements:

Or you may have your own favourite scenes from movies or from books that show specific aspects of well-written stories. One important thing here is to strike a balance between giving people an interesting challenge and giving them such a difficult task that they ignore it and walk away. People are not interested in trying to become novelists in one session; just give them a taste of some of the interesting things they can do while constructing a story together. If you have enough time, another interesting thing to do is to have people stop the exercise after three or four tellings, discard the story completely, and start all over again with new anecdotes but with the same underlying message. This is a good way to help people come at the issue from another direction and delve deeper into it. |

Uses and applications

- The act of creating a purposeful story can be a valuable integrator of anecdotes in order to discover patterns in them and to reveal larger truths. A purposeful story is a social construct rich with complex meaning, much like a family of archetypes or a Cynefin framework, and as such can be used to think about situations and questions.

- Constructing purposeful stories is a useful way to build communication narratives that can convey complex understandings in a form that is memorable, motivating and persuasive.

Do's and Don'ts

Simple bulleted list including common mistakes

Virtual running

Default is to state that it cannot be until we have developed and tested practice. If it can be run virtually then we describe it here.

It is acceptable to add a third column to the workflow if needed

Articles

Specific articles can be referenced here

Blog posts

Link with commentary

Cases

Link to case articles here or third party material

Method card material

This material will be extracted for the method cards

Possible symbols or illustrations

Front page description

The story construction (standard fable) method structures and accelerates the natural process of story creation, for integration and communication of complex messages.

Back of card summary

This method replicates the way that we create stories through telling and retelling over time, but speeds up the process by adding deliberate structure. Purposeful stories can convey complex understandings in a memorable, motivating and persuasive form. The method can teach a basic skill, help determine communication strategy and/or integrate material created in a workshop. Through integrating anecdotes in the process of story creation, we can discover patterns and reveal larger truths. A fable is a long and complex story whose message is memorable but whose details are not.

How can it be used?

for diagnosis

for analysis/understanding

for intervention

Method Properties - Ratings

Represented by symbols - interpretation/voting scales are:

References

Link to other articles on this wiki if they are relevant.