Habits

Habits are actions or meanings that can be created, or emerge. They are accustomed practice that you know so well or have experienced so often that it seems natural, unsurprising, or easy to deal with. Habits can be rendered useless but persist regardless. In general habits are about energy efficiency at an individual and community level.

Overall we need to understand them, map them, and be proactive in managing them. We may not be able to map directly what a habit is, or its function, but we can map where we need to know that they are in play.

For example Ann Pendleton-Julian took her concept of scaffolding and Dave Snowden’s idea of dark constraints to talk about the complex structures that build up around extreme sports. We can’t see everything that goes into current practice, but we know we want to work with those who have the experience and the habits that make you safe. Therefore, we could also call this dark habits (like dark constraint or dark matter) where we can see an effect without being able to see a reason for the said effect.

The individual is not always the primary actor. Communities evolve habitual practice over the generations and while it can be a cause of unnecessary conservatism, more often it has high utility and you ignore it at your peril. The desire to ignore the past and start afresh each time means that much of value is lost because those involved in the practice are unaware of what they did, or they took it for granted that anyone with experience would understand.

Name and History

Carlisle identifies two schools in philosophy – those who think habit is an inhibitor, “a rut we get stuck in” and those who think it is essential to create a degree of order and also that it acts as a liberating force. We take the stance that it is both, habit is a part and parcel of what we are as a species for good and bad.

Carlisle makes a distinction between individual habit and customs. Individual habits are often contagious, we pick up many habits, physical, linguistic and behavioural from family. All of this makes sense in terms of energy efficiency. Customs also are a part of culture and key to identity, they specifically provide a sense of belonging and are acted on explicitly and with awareness.

Linked to this we have a distinction between active and passive habituation. One side of that is becoming accustomed to something or learning to live with it (passive) which on the negative side includes things such as bullying. In contrast, in trades and professions, the process of acquisition of habit is often built into training and early work experiences.

Habit can also either be a source of action, a result of action, or indeed both. Repetition is key here and that repetition may be observed as well as experienced.

Finally, we get the distinction between habit as “an aptitude, skill or facility”, and habit as a “tendency or inclination.” Again repetition is key with some habits being formally learnt over time (e.g. how to ride a bike with cleats) while others are more compulsive and more difficult to manage (e.g. saying “yeah” or “um” in sentences or excessive food consumption).

Mapping habits

Understanding habits (and rituals) improves our understanding of decision making, not in the sense of cognitive rational processes but looking more widely including intuition and non-cognitive decision making.

Habit and ritual provide low energy cost capability that should free us up to better handle novelty. Of course, we don’t want to be trapped by custom and practice but neither do we want to reject, without caution, the value of more traditional and implicit processes and practices.

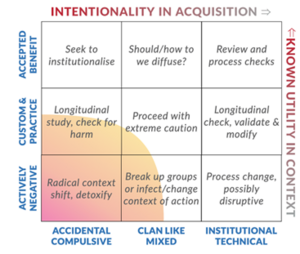

Habits can be understood and mapped on a 3x3 matrix comparing intentionality in acquisition with known utility/use (utility is always contextual and the knowledge of utility needs to include an understanding of context). How to understand each box is described below.

Accepted benefit (top row)

- Accidental-compulsive: Everyone can see the value of the habit, but it was never designed, it’s just emerged over time. That means it's important but vulnerable to loss. Shifting it to the right (ritual is one way) is called for, but with care for context. Just because it works here doesn’t mean it will work everywhere.

- Clan like, mixed: This means the practice is a part and parcel of a group of people. That group may represent profession or practice but they have developed habits of behaviour and have forms of practice that institutionalise these within a group. That may include initiation rights both positive and negative (e.g. hazing).

- Institutional, technical: This is a part and parcel of the way we do things. Acquisition of habit may go right back to induction or even recruitment. The danger here is retention beyond utility on the one hand, and neglect due to familiarity on the other. Therefore making such practices explicit is important. You also need to think about practice to acquire capability, rather than training in a capability.

Custom and practice (middle row)

We used this title to convey a degree of ambiguity, they are there but we are not sure why. They may be defended by users but they typically find it difficult to do to an outsider. As a general principle we need to study these over extended time periods. In the context of use we may see what practice emerged but it may not be there for recall outside of that context. Genba may be particularly useful here.

- Accidental-compulsive: The key question here is to check for harm, that is the trigger to ask a second question as to if the practice is harmful in all contexts and if it is, action needs to be taken. It’s an early warning sign of something shifting to actively negative. If it isn’t then leave well alone and see what comes out of longitudinal study.

- Clan like, mixed: This is the main danger area, the practice is institutionalised so it's more likely that it has a purpose, but that purpose may or may not be a good one. Hazing ceremonies have utility in creating groups but they can become a tool for sadists, to take just one example. Here we have the highest danger of abandoning something, and the highest danger of not destroying it.

- Institutional, technical: This one is probably not a danger, but it may be an inherent part of the culture and we should test for utility. At this level of adoption change is going to be gradual; seeking adjacent possibles has the advantage of reducing the risk of change.

Actively negative (bottom row)

- Accidental-compulsive: This is the space of addiction e.g. in companies where a particular person (not always in a leadership position) is basically a bully. Here an HR department may actively avoid dealing with misogyny in technical groups because the cost of replacement is high.

- Clan like, mixed: This is a variation on the above, but it has become institutionalised with a group or practice. It can be an exclusionary mechanism and again is often unarticulated. It may stifle innovation because people aren’t prepared to take a more open approach – they simply can’t see the point.

- Institutional, technical: Here we can range from toxic cultures where the best solution is to leave, or something less immoral but more dangerous e.g. when IBM handed over the IP to Windows to Gates, thereafter the culture was paranoid about IP to the point where it stifled partnerships and innovation. Mapping of paranoia triggers may be one way to deal with this.

Related

Principles

- Rituals reinforce habits and trigger or break habitual behaviour. They are particularly useful for institutionalising positive habits.

Frameworks

References

Articles and books

- Clare Carlisle’s 2014 book On Habit

Blog posts

- Dave Snowden, Twelvetide 21:01 of habits, The Cynefin Company Blog (December 25, 2021)