Vector theory of change

Introduction

If we want to manage complex environments, we need to stop talking about how things should be in the distant future, and start changing things in the here and now. Move from lofty long term goals to mapping where you’re at and making small changes and monitoring what’s happening. Here is a brief explainer on vector theory of change.

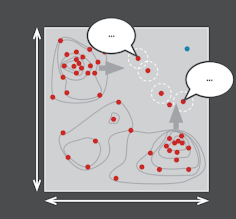

We decide on what direction we want to go in, map the system’s current state, run experiments to shift in that direction, measure the system's state again and assess what interventions might be most useful. This is an iterative process that incorporates feedback and allows for continually taking stock of a dynamic environment so we can take advantage of new opportunities as they arise. Hence, this is a ToC (Theory of Change) that is most suitable for complex environments.

With this approach, we talk about vectors, rather than explicit goals and end points. Hence, the name vector theory of change. A vector integrates three factors: the direction you want to move in, how quickly, and how much effort will be required. We start journeys with a sense of direction in which we want to move, we consider the intensity of effort that specific paths will take. Then speed is set by identifying available resources and natural enabling constraints to achieve the lowest energy costs to move in the desired direction.

List of methods / Generic sense-making

Background

A Theory of Change (ToC) is the theoretical underpinnings of a social intervention/plan to change something. The theory can be based on experimental evidence or logic. It can refer to a collection of approaches aimed at strategic planning, description, monitoring and evaluation and learning,[1] that describe the steps needed to achieve a long term vision by considering the causal links underlying these steps. [2]

The most common approach to ToC involves visioning what you want to achieve, and then working backwards in steps outlining the actions needed to achieve the subsequent step until you reach the present moment. This is a useful approach when working within a system that could be categorised as clear or complicated within the Cynefin domains. However, this approach to ToC will not be useful when operating within a complex system given its dynamic nature.

Origins

The origins of the theory were when running a war games simulation in Singapore, using a 3D model of the battlefield. There was a need to see the big picture as well as the small changes and this need led to landscapes, although landscapes also had longer origins. This big picture became referred to as the Dispositional Landscape and represented the current state of how people are disposed to act as well as clusters of behaviour or attitudes and are shown in 2D as opposed to the 3D of the war game simulation, which confused people. These landscapes reverse the landscapes of evolutionary biologists who believe you have to climb a peak whereas a Dispositional Landscape has deep Attractor Wells which are hard to escape. The concept of these landscapes were tested with Stuart Kauffman, whose Fitness landscapes show the ability to jump between different conditions.

Adjacent Possibles

The data points that lie in between each of these clusters and the ideal are called ‘adjacent possibles’. Respondents’ data points correspond to their stories that reveal insights into the location and context of the data points. Using insights from the adjacent possible stories, interventions are created that may shift people in the clusters towards the adjacent possibles, thereby getting them closer to the ideal point. Adjacent possibles act like stepping stones, making it easier to cross a wide river rather than attempting to cross in one big jump. And so over time the data points should shift from their initial starting point, through the adjacent possible to reach the ideal point.

Uses of Dispositional Landscapes

- Helps you see the big picture

- The depth and gradient of Attractor Wells are represented using contours, as you would see on an Ordnance Survey map. Dense contours represent and identify clusters which are difficult to shift, whereas if the contours are shallow it identifies clusters which are easier to shift.

- Another use of the landscapes is to understand similar dispositions, behaviours or attitudes as stepping stones from the current state - so called Adjacent Possibles.

If no stepping stone exists or none are close enough to the current state, Scaffolding is needed. You may want to move in a direction, but how you do it is your own affair.

Coherent or Incoherent

After creating a Dispositional Landscape you can see the disposition of culture. It enables you to identify at multiple different layers, where there may be an issue or problem and what change is possible right now.

You need a map before you can start a journey, with a map you can understand the nature of the journey. Is it going to be a difficult uphill journey, or are the Energy Gradients with you and might a few small tweaks have a massive effect.

In the UK, when all the political parties were the same, the energy gradient and entry point for extremist views was low. If there are very shallow attractor wells it is easy to shift to an adjacent possible. These gradients also link with identity. If there is no clear identity, no strong affiliation, people will have an increased disposition to be more promiscuous.

Consider the clusters of a landscape and ask questions:

- Coherent homogeneity - Are we different but in a coherent way?

- Incoherent homogeneity - Are we all the same, dangerously so?

- Coherent heterogeneity - How much heterogeneity is needed to be resilient in the current context? To be coherent, are the different clusters overlapping? Understand at a fractal level, are we together or disparate on a subject? In a crisis everyone needs to be together.

- Incoherent heterogeneity - How many clusters are there that don’t overlap?

Narratives approach

The narratives element of the naturalising sense-making approach asks the question ‘How do we create more stories like this, less like that.’ In saying ‘more like this’ or ‘less like that’ this refers to a grouping or cluster of stories not individual stories.

When making interventions to create shifts, these must done be within peoples own competency level and the decision making this drives is referred to as ‘Fractal decision making’. These decisions of ‘more like’, ‘less like’, are at the agent's own level of competence. You’re empowering them to come up with something that works for them, or to deal with something in which they are competent, rather than something idealistic that’s been created by a limited number of people who are not directly involved.

In empowering people to make decisions at their own level of competence, we recognise that different clusters are in fact, different, so average targets don’t work. Agents are able to go in their own direction, but the system as a whole converges at a high-level. What happens is the fractal patterns converge in a common direction.

This approach was used in the Trios in the South Wales Valleys. Where the result of shifts are stories and if these reflect moving in the ‘right direction’ all is well. If they do not, adjustments can be made and this ability to make adjustments is what makes the shifts within a portfolio of projects safe-to-fail. This approach towards change is a new way of using Commanders Intent or Einheit (unit in English). It is error tolerant as course corrections can be made along the way while still acknowledging the direction or intention.

Action-based over Language-based change

This supports a needed shift to action-based change from one that is language-based change. A couple of examples of language-based initiatives or ones that use soundbites are ‘Customer first’ or ‘staff are our biggest asset’. Language-based change results in platitudes and those people that can best use language are most able to game this approach and win i.e. to parrot the language without acknowledging or acting on the intent.

Distributing the decision-making, but not the authority, and doing something, that is taking action, increases the agency of those who are involved. Traditional approaches privilege the elite few and disenfranchise the rest. It helps if you can focus on how to create more stories like this and fewer like that.

Nudges and small actions

This mode of change could be compared to ‘Nudge economics’[3] Nudges are small, contextual interventions that change the decision-making context, rather than offering incentives. Typically nudge theory is used by decision-makers who want to achieve a specific outcome. They use environmental changes or messaging to move citizens toward this ideal endpoint. With this soft paternalistic approach, citizens are really being pulled towards someone else’s preferred state with no dialogue or opportunity to voice their preference on what the desired outcome should be in the first place [4] [5] [6], not to mention how that change could be achieved.

With this revised approach it’s about identifying and attending to the little things that make a big difference, not the big things that don’t. Initiative fatigue is a major issue and aspirational visions of the future and outcome-based targets, as stated in Goodhart's Law and simplified by Maralyn Straham, measures cease to be useful as people game them. Another problem is explicit goals destroy intrinsic motivation.

Instead of the traditional approach, working with the small things that people understand, within the context of their competence level and ability to actually control things will make a difference. Shifting away from idealistic and aspirational views of how things should be.

This approach is not..

- It is not about or advocating distributed authority. It is about devolved or distributed decision-making. Devolved authority still results in narrow distribution of power, just at a lower level, and distribution of sense-making is still low as a result.

- It is not about telling people what you want to achieve. It is about empowerment and delegation of decision-making, with subsequent course correcting if bad things do happen. That’s an important point and distinction to make.

- It is not about explicit instructions which people can say they did, but can also game. It is about, using a Commanders Intent language based on the stories everyone across the organisation knows. ‘We need more like ‘Things Colonel Strong did at Little Roundtop’. It’s very difficult to game a narrative metaphor as it has a much richer context.

Mapping culture - A Gaping Void example

Steps:

- Create a wall of Gaping Void cartoons/illustrations.

- Choose 6 that represent desired organisations.

- Everyone then chooses their favourite image for a desired or undesired state or both.

- Tell a story of why that’s the case.

- Interpret the story

- Tell a story of what it would be like in the future.

In a single capture you get:

- Situational assessment and

- Micro-scenario planning

From this you can draw the maps at a fractal level.

Designing an intervention

After following the above steps, designing the intervention should be done by the people in the system - not a set of external analysts, consultants, or managers. When people are shown the stories, people recognise the stories and ideas for interventions come quickly.

- Provide the stories to people who have any level of agency in the situation.

- Ask them "what would you do to create 'more like these and fewer like those.'"

- Verify the probes are safe-to-fail and how they will be monitored.

- Let the people get on with it and get out of their way.

References

- ↑ Ringhofer, L., & Kohlweg, K. (2019). Has the Theory of Change established itself as the better alternative to the Logical Framework Approach in development cooperation programmes?. Progress in Development Studies, 19(2), 112-122.

- ↑ Taplin, D. H., & Clark, H. (2012). Theory of change basics: A primer on theory of change. New York NY: ActKnowledge.

- ↑ Thaler, Richard; Sunstein, Cass (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300146813.

- ↑ Sætra, H. S. (2019). When nudge comes to shove: liberty and nudging in the era of big data. Technology in Society, 59, 101130.

- ↑ Jones, R., Pykett, J., & Whitehead, M. (2011). The geographies of soft paternalism in the UK: the rise of the avuncular state and changing behaviour after neoliberalism. Geography Compass, 5(1), 50-62.

- ↑ Yeung, K. (2017). ‘Hypernudge’: Big Data as a mode of regulation by design. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 118-136.